While it’s debatable whether or not barbecue was actually born in South Carolina, what is beyond question is the fact that African Americans have played a defining role in its development from the very beginning.

The sad thing is that like so many of the contributions blacks have made to the American experience, their role in the establishment of barbecue is at best given lip service, and at worst, those contributions are whitewashed or ignored completely.

This historic reality jumped out from the shadows in July 2015 when Fox News published their list of “America’s most influential BBQ pitmasters and personalities,” a questionable list to begin with and one that included only white folks.

Such a blatant oversight caused a bit of a stir, but the thing to understand is that such exclusions and marginalizations have long been standard fare.

Writing for CNN’s Eatocracy back in 2012, three years prior to the Fox News debacle, author Adrian Miller pointed out that these popular newspaper and magazine lists and TV features largely disregard African Americans.

“What’s regularly missing in these features are shout-outs to African Americans,” Miller writes. “Such omissions are troubling given the overwhelming contribution that African Americans have made, and continue to make, to the American barbecue tradition.”

In reaction to the Fox News story, food historian and Southern Living BBQ Editor Robert F. Moss penned an article documenting the “15 most influential figures in American barbecue history.”

He began with this:

1. The Unknown Barbecue Cooks

Unfortunately, the names of many barbecue pioneers have been lost to history. By the time of the Civil War, Southerners had been cooking barbecue for more than two centuries, and a great many of these cooks were African-American slaves, who tended the pits at barbecues organized for the white community as well as at events for their own families and friends.

After the Civil War, thousands of talented cooks in rural areas and small towns brought delight to generations of hungry Southerners, but their names didn’t make it into newspapers and other historical records. We may not know who they were, but we know they were there.

Who Invented Barbecue?

Let’s be clear: we would likely not enjoy the barbecue traditions we know today if it had not been for the early role of enslaved and marginalized people of color, even if those contributions were not devoid of European influence.

As Saddler Taylor, Folklorist for the McKissick Museum at the University of South Carolina, wrote the following in his essay High on the Hog:

“To understand barbecue history in the Palmetto State is to acknowledge the contributions of multiple traditions — African, Native American, and European. Once separate streams, these traditions flow together early in our history to form the mighty river that is South Carolina slow-cooked pork.”

And while we agree that barbecue did not evolve in a vacuum, we also acknowledge the obvious: the folks doing most of the actual work of cooking in those early days were not white. Naturally, the American barbecue tradition evolved largely through the skills of those tasked with creating it.

To appreciate the impact of this, you have to understand the history of barbecue.

A Brief History of Barbecue

It’s widely believed a traditional cooking technique used by the indigenous people of the Americas, first recorded when Europeans were coming into the “New World,” formed the basis of what would become Southern barbecue.

On his blog History South, historian Dr. Tom Hanchett writes the following:

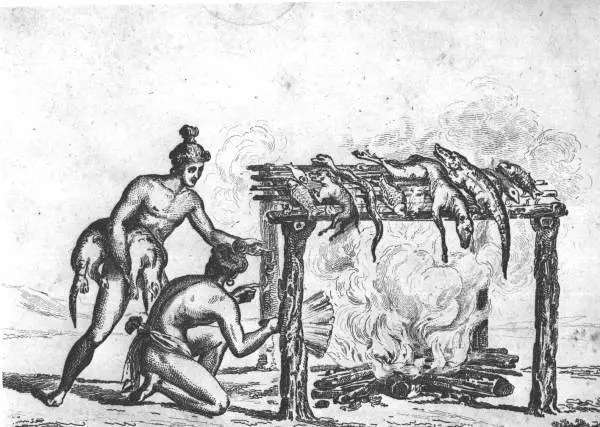

When Columbus showed up in 1492, he noticed Indians slow-cooking meat, a practice they called barbacoa. A 16th-century painting by French explorer Jacques Le Moyne shows Indians in Florida laying out their diverse game – fish, mammals, and reptiles alike – on a framework of wooden stakes erected over burning logs.

George Washington, procuring meat for his troops during the French & Indian War, spoke of “barbecuing it in the Indian manner,” and barbecues became popular political campaign events in the days of the Founding Fathers.

The Barbacoa

Where did the name barbecue come from?

Both the name BBQ and the style of cooking came from the native tribes of the New World because of their use of the barbacoa.

Barbacoas are often credited to a sub-tribe of the native Arawak people called the Taino because this is with whom Columbus first encountered the term. By his arrival, however, the use of the barbacoa was widespread among tribes from what is now North America through the Caribbean and into South America.

Image credit: Florida Photographic Collection

These wooden platforms were built of green wood and were used to keep the animals they were preserving several feet above a low fire. Based on reports from other explorers, the word barbacoa actually seems to be the term for the structure itself and could refer to any sort of similarly-constructed loft meant to keep things above ground, such as a bed.

Nonetheless, it is widely held that the term barbacoa is the origin of our word, barbecue.

The First Recorded Barbecue

The first known written description of pork barbecue may have occurred in Mississippi.

“According to Faulkner’s County: The Historical Roots of Yoknapatawpha, 1540-1962 by Don Harrison Doyle, in December 1540, near what is now Tupelo, Mississippi, [Hernando] de Soto collaborated with the Chickasaw tribe on a feast featuring pork from Spain cooked on a barbacoa.”

The problem is that while Doyle’s book does state that de Soto camped near the Chickasaw and tried to establish a rapport with them, it never actually says anything about a barbacoa or any cooking technique in reference to the “feasts” that were enjoyed between the two.

Here is all that Doyle writes about it:

“The Chickasaws had no domestic animals and had never before it tasted anything like the pork the Spanish roasted for these feasts.”

Of course, Lake High, in his book A History of South Carolina Barbeque, contends that this marriage of pork cooked slowly on a barbacoa may have first occurred in South Carolina, at what is now Saint Helena. However, that contention hinges upon the Spanish, their pigs, and native tribes meeting in the 1560s.

Doyle’s account seems to pre-date High’s assertions by some two decades. It doesn’t seem like much of a stretch to conclude a pig was cooked upon a barbacoa at sometime in the previous decades, but we cannot be certain.

Regardless, it is widely accepted that the Spanish explorers adopted both the term and the cooking technique and helped spread the combination in what is now the southern US, where it eventually made its way to the English colony of Virginia.

The Rack-Masters of Barbecue?

What seems less clear is how, where, and when an important transition occurred.

The barbacoa is a raised rack made of green sticks. Today, we don’t have a single “rack-master,” and you never hear the phrase in popular culture. These days, those skilled in making barbecue are considered “pitmasters.”

Why is that?

It seems logical that pitmasters are so named because barbecue made the transition from the rack to an earth-dug pit.

In fact, if you google “barbacoa technique,” what you’re going to find is a lot of articles or recipes about meat cooked while buried in the ground, particularly in Mexico. But that doesn’t make any sense given what we know about the original barbacoa.

If you look at early illustrations of barbecues in the South, you’ll find earth-dug trenches with green wood saplings holding up whole animals. Somehow, barbecue moved from a raised platform made of wood down to — or into — the ground.

I asked Moss what he might know about this transition. Here was his reply:

Not a lot, unfortunately—there’s a sort of “missing link” between the Native American technique and what we would think of a Southern-style pit barbecue. The problem is there is almost nothing written in the 18th century (surviving, at least) that captures how barbecue was cooked nor how it might have evolved from the rack of sticks to the in-ground pit method.

Some have assumed that it must have evolved somehow from one to the other. Others have speculated it was more just colonists borrowing the Native American word and not the technique. I don’t think there’s enough evidence one way or another to say.

If you think about it, though, it would be pretty difficult to build a frame of sticks that would hold, say, a whole hog or steer, versus fish or small mammals, which is what Native Americans cooked on their “barbacoas.” Much simpler and more reliable to bring it down to the ground and lower the coals by digging a pit.

Moving from a raised rack to the ground seems like an inevitability, both a logical and practical decision. While we have no documentation of how or when this change occurred, the move set the stage for the next evolution of Southern barbecue.

History of Barbecue and Slavery

By the early 1600s, the practice of enslaving Africans had begun in the English colonies. While 1619 — the year the first captives arrived in Jamestown — is often cited as the beginning of slavery in what is now the US, there is credible evidence to suggest enslaved Africans certainly touched our shores much earlier.

According to Michael Guasco writing for smithsonianmag.com, “In 1526, enslaved Africans were part of a Spanish expedition to establish an outpost on the North American coast in present-day South Carolina. Those Africans launched a rebellion in November of that year and effectively destroyed the Spanish settlers’ ability to sustain the settlement, which they abandoned a year later.”

(Might the pig and the barbacoa have first met then?)

Regardless of when the practice of slavery officially began on these soils, we have a clear history of enslaved Africans working for the Spanish explorers in the 1500s and a knowledge that they were forced into labor in Virginia in the early 1600s.

In both cases, it seems a safe assumption that these enslaved people were the workers responsible for menial, laborious tasks such as cooking. Therefore, it is logical to conclude that these same people were the ones interacting with the indigenous peoples, learning their craft.

As Shontel Horne writes in “Black Pitmasters are Hustling to Preserve Barbecue’s Roots,” “To have a real dialogue about barbecue, you must first be prepared to have unsavory conversations about the United States…we wouldn’t be telling the complete story of barbecue heritage without acknowledging that the cooking technique was originally the byproduct of an exchange between Native Americans and enslaved Africans in the Caribbean beginning in the 16th century.”

It should not be overlooked that many Native Americans were themselves enslaved during this early period and therefore would have also been in close companionship with enslaved Africans, both with the early Spanish explorers and later with the colonists. (Note that Africans were also enslaved as “chattel” by indigenous tribes by the late 1700s, albeit encouraged by or because of European pressures.)

Did Enslaved People Invent Barbecue?

It is not a leap to conclude that given the natural interactions and cooperation that would have occurred between these two mutually subjugated peoples that the enslaved Africans would have learned and employed the Native American’s low and slow cooking technique.

As that technique is modified into a more practical approach using earth-dug pits for the weight of large, whole-animal cooking, enslaved Africans began setting the stage for the pitmasters of today.

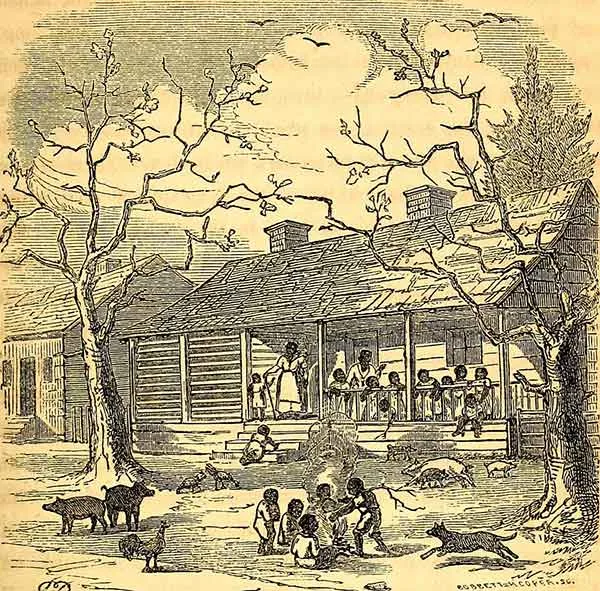

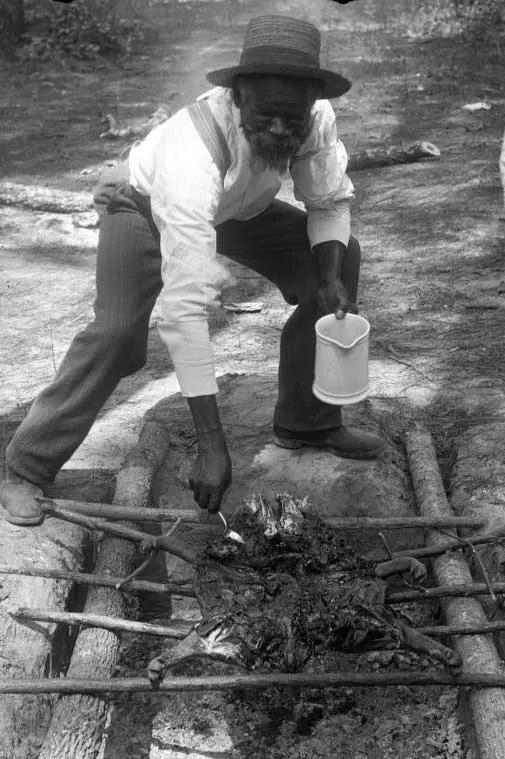

And while common sense tells us that the true pitmasters of this early era were the enslaved people, the truth of it is also documented in numerous images and wood carvings from the period.

When you’ve seen these images, the picture painted is clear: there is a trench, there are wood saplings placed across the hole, there are whole animals —usually pigs— butterflied and lain over the saplings, and there are one or more men of African descent manning the pits.

If any other person is depicted, it is usually a white man clearly not dressed for labor. In fact, given the early origins of barbecue, it is more likely he is dressed for a special occasion.

The Plantation Barbecue

Consensus holds that what would become Southern barbecue as we know it began to flourish by the mid-1700s on plantations in Virginia and spread southward from there. It is also largely recognized that barbecues were not commonplace but rather generally held for holidays, special events, and political reasons.

This tradition has continued to the present day with barbecue being an important facet of many holidays and with BBQ restaurants throughout the South being an important destination for politicians running for office.

Let’s touch on the plantation, as this was the cradle in which Southern — and therefore American — barbecue was raised.

In “How the Black Creators of Barbecue Were Erased From History,” author Max Watman interviews Black Smoke author Adrian Miller. In it, Watman pointed out the following:

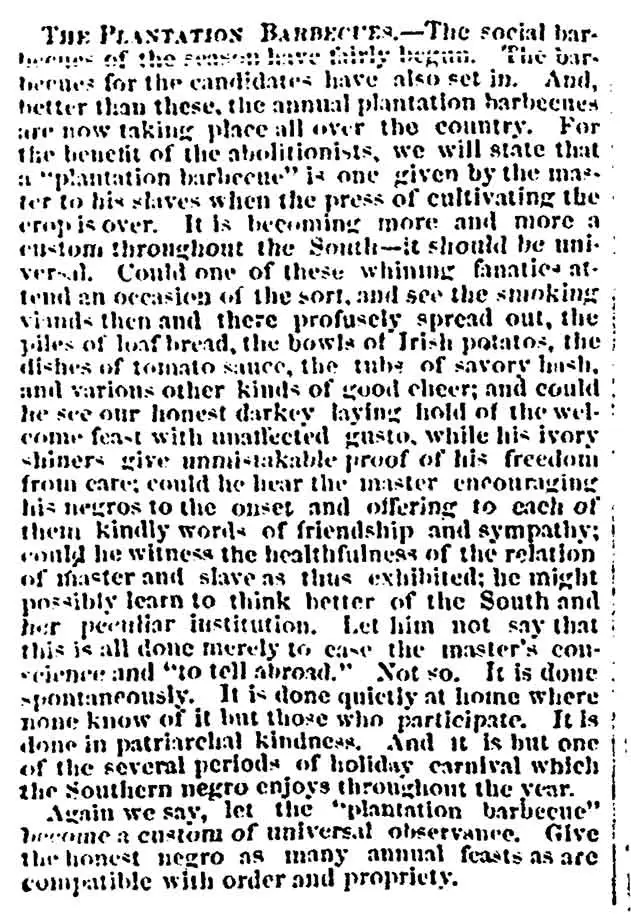

By the 1830s, in order to have legit barbecue, it was thought, an African American cook and his crew were necessary and barbecue was understood to be a Black experience. Miller explained a complicated twist in the narrative in words far more polite than I might have chosen: “In the 1850s, as there’s more and more tension about slavery, you actually find pro-slavery advocates using the plantation barbecue as evidence of their generosity.”

In fact, a piece entitled “The Plantation Barbecues” published on July 12, 1860, in the Charleston Mercury provides evidence of just that. The author writes of the great camaraderie between the races that the “whining fanatics” (abolitionists) would see and the “patriarchal kindness” provided to the enslaved on such occasions.

Here’s an excerpt from the article (seen below):

“…and could [abolitionists] see our honest darkey laying hold of the welcome feast with unaffected gusto, while his ivory shiners give unmistakable proof of his freedom from care; could he hear the master encouraging his Negroes to the onset and offering to each of them kindly words of friendship and sympathy; could he witness the healthfulness of the relation of master and slave as thus exhibited; he might possibly learn to think better of the South and her peculiar institution.”

Evidence of their generosity, indeed.

Origin of the Term Pitmaster

We know that by this era, enslaved Africans are the labor force and would have been the ones working the earth-dug pits being used to cook whole animals, a laborious job. In practice, if not in name, these men were the first true pitmasters.

As Grady Atwater, administrator for the John Brown Museum, notes in his article “BBQ roots are connected to slavery,” the word pitmaster itself once had a different meaning.

“The term ‘Pit Master’ refers to an elderly slave who was an expert cook and led the effort to prepare the BBQ for the slaveholders. Younger slaves worked under the ‘Pit Master’ to learn how to prepare a whole hog for a BBQ.”

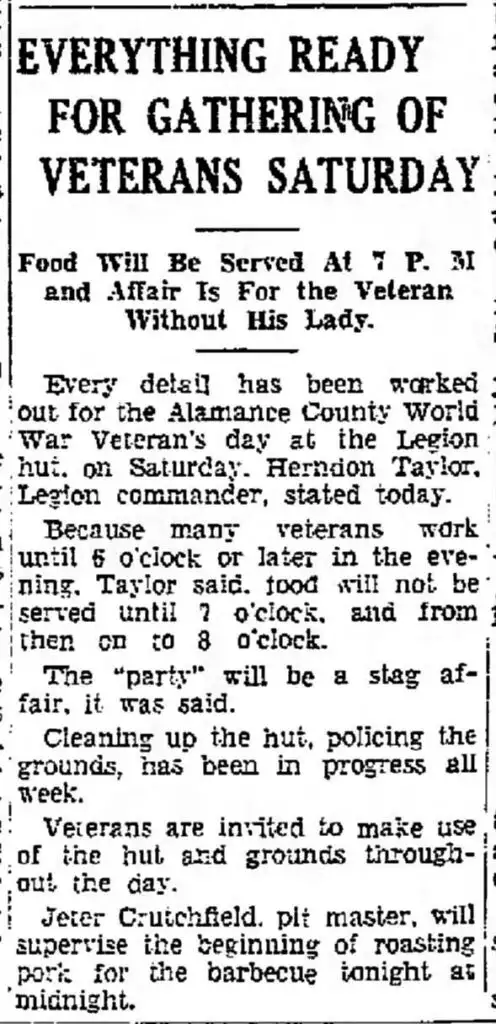

While Atwater states that the term pitmaster was born in the dark times of enslavement when these elderly cooks were barbecuing using earthen pits, the earliest known printed reference to a pitmaster was published on September 22, 1939, by the Daily Times-News of Burlington, North Carolina.

They wrote, “Jeter Crutchfield, pit master, will supervise the beginning of roasting pork for the barbecue tonight at midnight.”

Crutchfield, it should be noted was a white man. All along, however, it was not uncommon for white men to be the face of local barbecue. More often than not, the ones doing the actual work were African American. Note the article specifies that Crutchfield “will supervise.”

Regardless, what it tells us is that the term pitmaster had become common enough in usage to have found its way into a newspaper article by the 1930s. So the pits were a defining characteristic of the process.

The Earth-Dug Barbecue Pit

Dr. Howard Conyers, NASA scientist, South Carolina native, pitmaster and whole hog barbecue expert, has looked deeply into the evolution of American barbecue. He points out that even up until the late 20th century these earth-dug pits were not uncommon.

Dr. Conyers writes about a realization that occurred to him on visits to black-owned BBQ joints in North and South Carolina:

“However, the real confirmation to me came when both men spoke of their fathers cooking BBQ in a hole in the ground. They described how they cook in the hole in the ground, nearly identical to how my father described to me as a child and later as an adult because that was how he learned to cook.”

This “hole in the ground” technique was widely employed in the black community up until the 1970s, according to Conyers. In fact, his father diagrammed the old pit design for him as an adult, and Conyers replicated the process in a demonstration on The Cooking Channel.

“Since I was raised in a community where this has been an ongoing technique since my ancestors’ enslavement,” said Conyers, “it is my responsibility to carry this tradition forward so America can see who perfected this craft before the era of modern, above-ground pits and smokers.”

And while these recreations maintain a history that is important to remember, it should also be noted that they are not our only proof of their lineage.

Barbecue References in Slave Narratives

In the 1930s, as part of the New Deal in the wake of the Great Depression, the Federal Writer’s Project was implemented in order to provide employment for historians, writers, teachers, and the like.

From 1936-1938, one set of these writers interviewed formerly enslaved people. This work was gathered to create the seventeen-volume Slave Narratives: A Folk History of Slavery in the United States from Interviews with Former Slaves.

While the interviews touch on numerous subjects, barbecue becomes a focus in at least a handful of them.

I present these excerpts from formerly enslaved South Carolinians largely as written (with only the n-word obscured), with apologies to anyone who may be offended by either the language or the content.

Stolen Pleasures

In an interview by Caldwell Sims in Union in late February 1937, Mrs. M.E. Abrams recalled a common practice among her enslaved relatives, stealing a hog to be barbecued on the weekends.

“Never mindin’ all o’ dat, we n’used to steal our hog ev’er sa’day night and take off to de gully what us’d git him dressed and barbecued. N****rs has de mos’es fun at a barbecue dat dare is to be had. *As none o» our gang didn’t have no ‘ligion, us never felt no scruples bout not gettin de ‘cue’ ready fo’ Sunday.

Us’d git back to de big house along in de evenin’ o’ Sunday. Den Marse, he come out in de yard an’ low whar wuz you n****rs dis mornin’. How come de chilluns had to do de work round here. Us would tell some lie bout gwine to a church ‘siety meetin’. But we got raal scairt and mose ‘cided dat de best plan was to do away wid de barbecue in de holler.

Conjin Doc.’ say dat he done put a spell oh ole Marse so dat he wuz ‘blevin ev’y think dat us tole him bout Sa’day night and Sunday morning. Dat give our minds ‘lief; but it turned out dat in a few weeks de Marse come out from under de spell. Doc never even knowed nothin’ bout it.

Marse had done got to countin’ his hogs ever’ week. When he cotch us, us wuz all punished wid a hard long task. Dat cured me o’ believing in any conjuring an’ charmin’ but I still kno’s dat dare is haints; kaise ever time you goes to dat gully at night, up to dis very day, you ken hear hogs still gruntin’in it, but you can’t see nothing.

While this commentary provides an interesting look into the culture and beliefs of one group of enslaved people, it also suggests something else: they made the barbecue themselves, without any overseer directing the work. It is pretty clear that the act of prepping and cooking these hogs was done only by the enslaved participants, implying they had the know-how themselves.

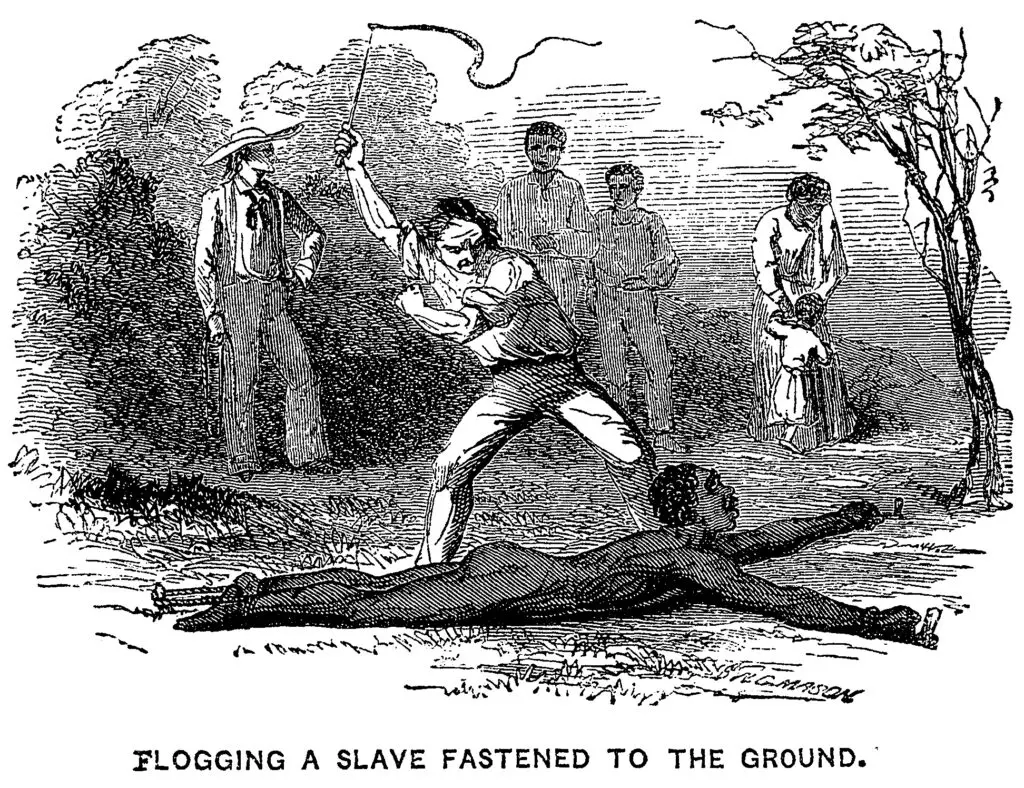

But it should be pointed out that the act of stealing a hog could be met with unbelievably brutal consequences.

Dangerous Consequences

In 1837, a book was published entitled Slavery in the United States. A Narrative of the Life and Adventures of Charles Ball, a Black Man, Who Lived Forty Years in Maryland, South Carolina and Georgia, as a Slave Under Various Masters, and was One Year in the Navy with Commodore Barney, During the Late War.

Yeah…that’s a heck of a name, but titles of such length were common practice at the time.

Anyway, the book recounts one scene relevant to our purpose, that of a stolen hog and the torture of slaves to discover the culprits and punish them.

Ball, the narrator, at the time of this incident was enslaved on a plantation in Georgia, but he was traveling to Savannah with his new “master.” This journey gave Ball the opportunity to observe life on various plantations where they stayed during the trip.

In this case, the pair were staying on the plantation of an unnamed “gentleman.” As was his practice, Ball was talking in the kitchen with some of the enslaved people on this estate when many were abruptly summoned by the overseer.

“The black people were all called together,” Ball recounts, “and the overseer told them, that some one of them had stolen a fat hog from the pen, carried it to the woods, and there killed and dressed it; that he had that day found the place where the hog had been slaughtered, and that if they did not confess, and tell who the perpetrators of this theft were, they would all be whipped in the severest manner.”

Despite their protestations of innocence, about 20 people were made to lie down, bare-backed, and the overseer lashed them with a long whip “by turns, until he was weary.” Turning his attention back to the first man, the overseer said he was certain the man knew who stole the hog, asked for the names, and, not receiving them, whipped the man again until he bled.

Cat-Hauling

Another “gentleman” there observing asked the overseer if he was confident the man knew the thieves and suggested “cat-hauling” the bleeding man in order to gain a confession. The overseer expressed his certainty and a willingness to try the man’s suggestion.

“A boy was then ordered to get up, run to the house, and bring a cat, which was soon produced. The cat, which was a large gray tom-cat, was then taken by the well-dressed gentleman, and placed upon the bare back of the prostrate black man, near the shoulder, and forcibly dragged by the tail down the back, and along the bare thighs of the sufferer. The cat sunk his nails into the flesh, and tore off pieces of the skin with his teeth. The man roared with the pain of this punishment, and would have rolled along the ground, had be not been held in his place by the force of four other slaves, each one of whom confined a hand or a foot. As soon as the cat was drawn from him, the man said he would tell who stole the hog, and confessed that he and several others, three of whom were then holding him, had stolen the hog–killed, dressed, and eaten it.”

The confession drew again the same punishment, with the cat dragged in the opposite direction this time, for the confessor and once in each direction for each of his accomplices, who were all then bathed in saltwater.

Unimaginable, but real.

While such accounts are beyond disturbing, it is also true that often barbecues were indeed a time of celebration, even for the enslaved.

The Holiday Barbecue

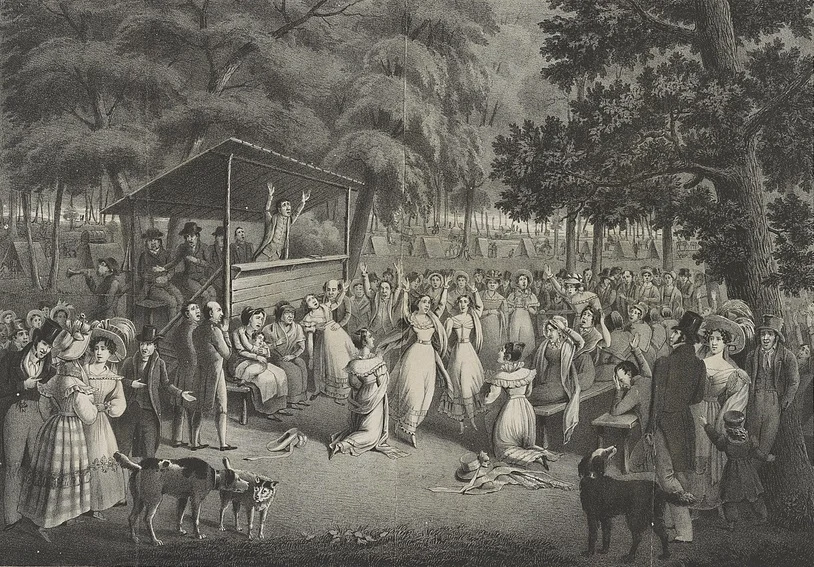

Gus Feaster, formerly enslaved himself, was also interviewed by Sims in Union. Feaster tells a grand tale of excitement and preparation for a 4th of July celebration and then a “Camp Meetin’” for the white families. (Camp meetings were akin to religious revivals.)

Feaster shared the following:

As you all knows de Fourth has allus been n****r day. Marse and Missus had good rations fer us early on de Fourth. Den us went to barbecues after de mornin’ chores was done.

In dem days de barbecues was usually held on de plantation of Marse Jim Hill in Fish Dam….Old Marse he give us de rations fer de barbecues. Every master wanted his darkies to be thought well of at de barbecues by de darkies from all de other plantations.

De had pigs barbecued; goats; and de Missus let de wimmen folks bake pies, cakes and custards fer de barbecue, jes’’zactly like hit was fer de white folks barbecue deself.

When company come like dey allus did fer de camp meetings, shoalts and goats and maybe a sheep or lamb or two was kilt fer barbecue out by Cilia’s cabin. Dese carcasses was kept down in de dry well over night and put over de pit early de next morning after it had done took salt.

Whilst de meats fer de company table was kept barbecued out in de yard, de cakes, pies, breads, and t’other fixings was done in de kitchen out in de big house yard* Baskets had ter be packed to go to camp meetin’.

Feaster’s somewhat nostalgic recollection paints the picture of these plantation barbecues and shines a bit of light on both the types of animals used and a little about the process.

A Dark Day

Of course, these Independence Day celebrations could be tainted by racism even after slavery was abolished.

Take the case of Jim Hutchinson, a “mulatto” freedman who served in the Union Army, worked as political activist, served as a trial judge, and became a land investor. Hutchinson met his death during a 4th of July celebration.

An Ancient Recipe Shared

You also see that in an interview Sims completed with Mr. Wesley Jones. In this piece, Jones provides us with what is our most insightful look at who is doing the cooking for these events and how it’s being done:

Courtesy of the State Archives of North Carolina

At de Sardis sto’ dey used to give big barbecues. Dem days barbecues was de mos’ source of amusement fer ev’ybody, all de white folks and de darkies de whole day long.

All de fiddlers from ev’ywhars come to Sardis and fiddle fer de dances at de barbecues. Dey had a platform built not fer from de barbecue table to dance on. Any darky dat could cut de buck and de pigeon wing was called up’to de platform to perform fer ev’ybody.

Night befo’ dem barbecues, I used to stay up all night a-cooking and basting de meats wid barbecue sass (sauce). It made of vinegar, black and red pepper, salt, butter, a little sage, coriander, basil, onion, and garlic. Some folks drop a little sugar in it.

On a long pronged stick I wraps a soft rag or cotton fer a swab, and all de night long I swabe dat meat ‘till it drip into de fire. Dem drippings change de smoke into seasoned fumes dat smoke de meat. We turn de meat over and swab it dat way all night long ’till it ooze seasoning and bake all through.

Lawyer McKissick and Lawyer A.W. Thompson come out and make speeches at dem barbecues. Both was young men den. Dey dead now, I living. I is 97 and still gwine good.

Dey looked at my ‘karpets. (pit stakes). On dem I had whole goats, whole hogs, sheep and de side of a cow. Dem lawyers liked to watch me ‘nint’ dat meat. Dey lowed I had a turn fer ninting it (annointing it).

Again, in this account, we see a couple of the themes reiterated: barbecue is for special occasions, barbecue is for political purposes, barbecue is cause for celebration and enjoyment, and barbecue is cooked by the enslaved.

What’s really exciting is that not only do we get a first-hand description of how barbecue was cooked, but we also get a vinegar-based barbecue sauce recipe from Mr. Jones.

His description provided the foundation for a recipe that food writer and historian Michael Twitty shared with us. We will include this recipe in the 2nd edition of our SC BBQ cookbook.

Just Like Yesteryear

There remains a lot of commonality between Jones’ account and today’s practices. Reading his descriptions, its hard not to think of Rodney Scott cooking whole hogs on his pits and the lineage back to Mr. Jones (and beyond) working whole hogs on his pits, isn’t it?

You have a spicy vinegar sauce being basted on whole animals over a bed of coals with a mop. There’s no more direct connection than that, but how did the practice bridge time and place?

Cotton Connection

Dr. Conyers has explored this idea and found a link. He contends that the technique spread from Virginia as cotton became king in the South.

In a video available on YouTube, Dr. Conyers lays out his research into the domestic slave trade and the growth of the cotton economy. He posits that the expansion of slavery paralleled the expansion of cotton across the South, and with it, the movement of barbecue traditions and techniques also follows.

In the video, he offers up imagery of earth-dug pits being used across the cotton belt, including one found in an archaeological dig at Montpelier, James Madison’s estate in Virginia.

On slides showing images of black men working pits from Virginia to Texas, Dr. Conyer recalls realizing why there was this connection:

When I think about barbecue, I always ask the question…why barbecue was found in Virginia, North Carolina, Florida, Georgia, and they all had these earth-dug pits…that looked almost identical. And then you go to Alabama, Louisiana, as well as Texas and you see whole animal carcasses being butterflied open and laid over a pit.

And so I start asking myself how is that the case? Because back during that era, you didn’t have YouTube and Google or any kind of books on how to do this. This knowledge actually had to go through the heads and hands of the people who were being traveled across the American South, and so during that time the people who were traveling and doing this actual work were in bondage.

However, Moss doesn’t necessarily agree with Dr. Conyers’ assessment (which may be due in part to my poor summary of it), pointing out that Charleston “had slavery from the beginning but never a culture of barbecue.”

However, I feel their theories merge on balance.

As Moss pointed out in response to my email, “In most cases, it was probably enslaved Virginians doing the cooking, and white Virginians certainly took slavery with them as they migrated, but barbecues were an entrenched part of Virginia social life and it migrated along with them as they set out for new opportunities on the frontiers.”

So, it would make some sense that Virginians migrated — at least in part — due to the spread of the cotton economy, taking their barbecue traditions with them.

Leaving the Plantation

As the country moves beyond the Civil War and the formerly enslaved find “freedom” — however limited and challenging this new condition might have been — they take their cooking talents with them as one of many skills with which they might eke out a living.

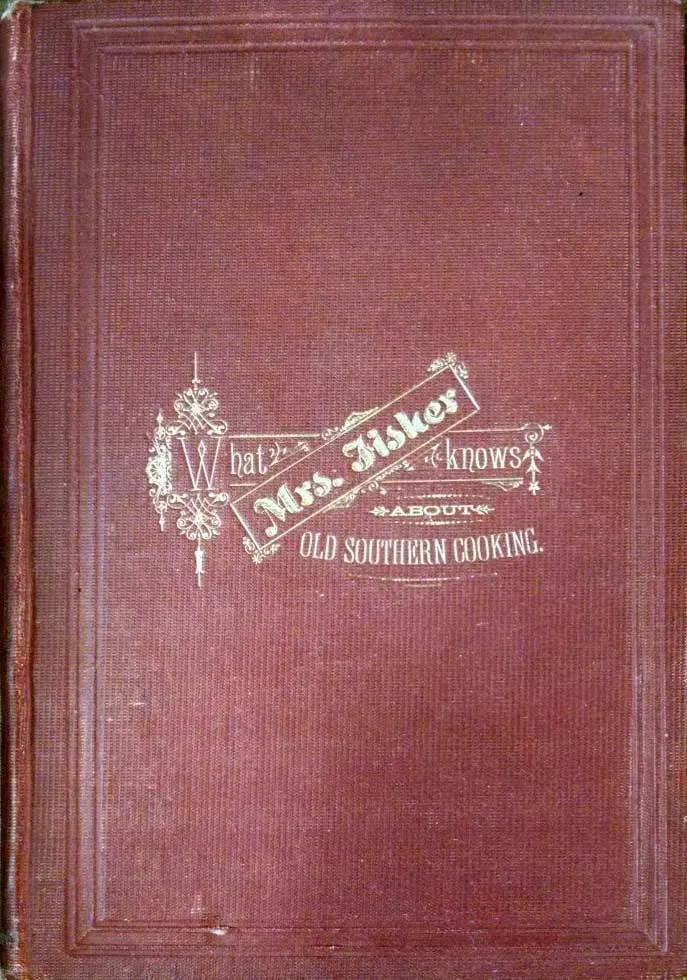

One such example comes from one of the first African American cookbook authors.

Born in 1832 in South Carolina, enslaved and raised working in plantation kitchens, Abby Fisher had developed her craft as a cook. After she gained her freedom, Fisher moved to Alabama briefly and then on to San Francisco.

There, she established a thriving business selling preserves and even won a bronze medal in 1880 at a local fair for her pickles.

In 1881, she published What Mrs. Fisher Knows About Old Southern Cooking with the help of others to whom she dictated the recipes. Mrs. Fisher was unable to read or write.

While there are no recipes for barbecue — not surprising, as that would have been done outside in pits by the men — one of the recipes in the book is particularly interesting.

The recipe is for a “Game Sauce” and includes a peck of plums, de-stoned and stewed with onions, vinegar, sugar, cayenne and black pepper, cinnamon, and salt. After a full day of simmering and close care, “You will find it the best sauce in the world.”

(This recipe will also be included in the second edition of our cookbook.)

Mrs. Fisher may have gained some acclaim, but most of the folks who continued the barbecue traditions established during slavery did not.

After emancipation, formerly enslaved peoples in the South enjoyed only a few years of relative prosperity and protection. But when the government abandoned them, many were forced back into subjugation through the implementation of sharecropping and other pressures.

Nonetheless, black BBQ traditions continued, even as more generations lived under constant threat. Black pitmasters had a high-demand skill, and as freed African Americans began to form their own communities within this new context, barbecue became integral to their culture.

Father to Son

Formerly enslaved black pitmasters passed their craft onto younger generations and those traditions continue to this day. That’s why Dr. Conyers’ father innocently drew a design in this century that depicted a cooking technique his forefathers perfected hundreds of years ago.

But during those intervening years, the truth of barbecue’s beginnings had been whitewashed, and those relegated to the shadows of society were ignored instead of being celebrated.

Twitty, speaking to a crowd at the American History Museum, shared the message he was taught of his ancestors as a child in school:

“Our food is our flag,” he said. “That’s why this is important. When I was growing up, I remember fifth-grade Michael Twitty was taught about his ancestors, like, oh, your ancestors were unskilled laborers who came from the jungles of West Africa. They didn’t know anything. They were brought here to be slaves, and that’s your history.”

Yes, those ancestors were taken captive and brought here to be enslaved, but not only did they know a thing or two, in spite of the most oppressive of circumstances, they contributed much to a country that built wealth from their labor, including barbecue.

Andy

Wednesday 11th of June 2025

Thanks for publishing this fascinating and disturbing history, Jim. What I find more upsetting than reading histories such as these are the attempts to ignore or deny them. We can't undo the past-- the first step toward redeeming it is to acknowledge it.

James Roller

Wednesday 11th of June 2025

@Andy, thanks for the kind words. As a retired teacher, I couldn't agree more.

Wednesday 6th of December 2023

Interesting that the vinegar red pepper sauce recipe is still used exclusively in eastern NC. Never changed. Tomatoes and ketchup are forbidden. Same whole hog process always served with potato salad and cole slaw with a side of hush puppies been eaten for over 200 years. And yes the best real pitmasters are black.

James Roller

Wednesday 11th of June 2025

Much the same in northeaster South Carolina. History and tradition carries on in food.